George VI on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

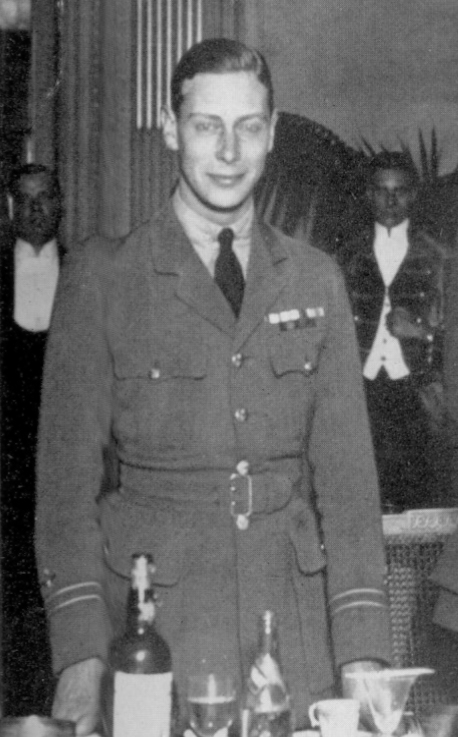

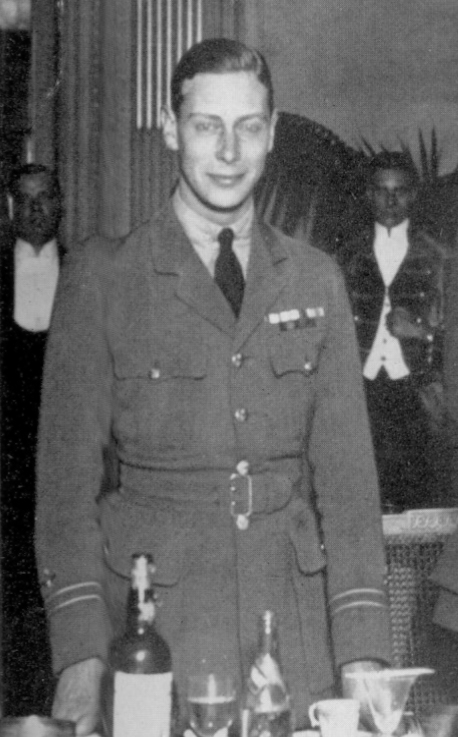

George VI (Albert Frederick Arthur George; 14 December 1895 – 6 February 1952) was

Albert was born at

Albert was born at

Beginning in 1909, Albert attended the

Beginning in 1909, Albert attended the

From December 1924 to April 1925, the Duke and Duchess toured

From December 1924 to April 1925, the Duke and Duchess toured

Albert assumed the

Albert assumed the  George VI's coronation at Westminster Abbey took place on 12 May 1937, the date previously intended for Edward's coronation. In a break with tradition, Queen Mary attended the ceremony in a show of support for her son. There was no Durbar held in Delhi for George VI, as had occurred for his father, as the cost would have been a burden to the

George VI's coronation at Westminster Abbey took place on 12 May 1937, the date previously intended for Edward's coronation. In a break with tradition, Queen Mary attended the ceremony in a show of support for her son. There was no Durbar held in Delhi for George VI, as had occurred for his father, as the cost would have been a burden to the  In May and June 1939, the King and Queen toured Canada and the United States; it was the first visit of a reigning British monarch to North America, although George had been to Canada prior to his accession. From

In May and June 1939, the King and Queen toured Canada and the United States; it was the first visit of a reigning British monarch to North America, although George had been to Canada prior to his accession. From

In 1940,

In 1940,

George VI's reign saw the acceleration of the dissolution of the

George VI's reign saw the acceleration of the dissolution of the

In the words of Labour Member of Parliament (MP) George Hardie, the abdication crisis of 1936 did "more for republicanism than fifty years of propaganda". George VI wrote to his brother Edward that in the aftermath of the abdication he had reluctantly assumed "a rocking throne" and tried "to make it steady again". He became king at a point when public faith in the monarchy was at a low ebb. During his reign, his people endured the hardships of war, and imperial power was eroded. However, as a dutiful family man and by showing personal courage, he succeeded in restoring the popularity of the monarchy.

The

In the words of Labour Member of Parliament (MP) George Hardie, the abdication crisis of 1936 did "more for republicanism than fifty years of propaganda". George VI wrote to his brother Edward that in the aftermath of the abdication he had reluctantly assumed "a rocking throne" and tried "to make it steady again". He became king at a point when public faith in the monarchy was at a low ebb. During his reign, his people endured the hardships of war, and imperial power was eroded. However, as a dutiful family man and by showing personal courage, he succeeded in restoring the popularity of the monarchy.

The

George VI

at the website of the Royal Family

George VI

at the website of the

King of the United Kingdom

The monarchy of the United Kingdom, commonly referred to as the British monarchy, is the form of government used by the United Kingdom by which a hereditary monarch reigns as the head of state, with their powers Constitutional monarchy, regula ...

and the Dominion

A dominion was any of several largely self-governance, self-governing countries of the British Empire, once known collectively as the ''British Commonwealth of Nations''. Progressing from colonies, their degrees of self-governing colony, colon ...

s of the British Commonwealth

The Commonwealth of Nations, often referred to as the British Commonwealth or simply the Commonwealth, is an international association of 56 member states, the vast majority of which are former territories of the British Empire

The B ...

from 11 December 1936 until his death in 1952. He was also the last Emperor of India

Emperor (or Empress) of India was a title used by British monarchs from 1 May 1876 (with the Royal Titles Act 1876) to 22 June 1948 Royal Proclamation of 22 June 1948, made in accordance with thIndian Independence Act 1947, 10 & 11 GEO. 6. CH ...

from 1936 until the British Raj

The British Raj ( ; from Hindustani language, Hindustani , 'reign', 'rule' or 'government') was the colonial rule of the British The Crown, Crown on the Indian subcontinent,

*

* lasting from 1858 to 1947.

*

* It is also called Crown rule ...

was dissolved in August 1947, and the first head of the Commonwealth

The Head of the Commonwealth is the ceremonial leader who symbolises "the free association of independent member nations" of the Commonwealth of Nations, an intergovernmental organisation that currently comprises 56 sovereign states. There is ...

following the London Declaration

The London Declaration was a declaration issued by the 1949 Commonwealth Prime Ministers' Conference on the issue of India's continued membership of the Commonwealth of Nations, an association of independent states formerly part of the British ...

of 1949.

The future George VI was born during the reign of his great-grandmother Queen Victoria

Victoria (Alexandrina Victoria; 24 May 1819 – 22 January 1901) was Queen of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland from 20 June 1837 until Death and state funeral of Queen Victoria, her death in January 1901. Her reign of 63 year ...

; he was named Albert at birth after his great-grandfather Prince Albert of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha

Prince Albert of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha (Franz August Karl Albert Emanuel; 26 August 1819 – 14 December 1861) was the husband of Queen Victoria. As such, he was consort of the British monarch from Wedding of Queen Victoria and Prince Albert, th ...

and was known as "Bertie" to his family and close friends. His father ascended the throne as George V

George V (George Frederick Ernest Albert; 3 June 1865 – 20 January 1936) was King of the United Kingdom and the British Dominions, and Emperor of India, from 6 May 1910 until Death and state funeral of George V, his death in 1936.

George w ...

in 1910. As the second son of the king, Albert was not expected to inherit the throne. He spent his early life in the shadow of his elder brother, Edward

Edward is an English male name. It is derived from the Anglo-Saxon name ''Ēadweard'', composed of the elements '' ēad'' "wealth, fortunate; prosperous" and '' weard'' "guardian, protector”.

History

The name Edward was very popular in Anglo-S ...

, the heir apparent

An heir apparent is a person who is first in the order of succession and cannot be displaced from inheriting by the birth of another person. A person who is first in the current order of succession but could be displaced by the birth of a more e ...

. Albert attended naval college as a teenager and served in the Royal Navy

The Royal Navy (RN) is the naval warfare force of the United Kingdom. It is a component of His Majesty's Naval Service, and its officers hold their commissions from the King of the United Kingdom, King. Although warships were used by Kingdom ...

and Royal Air Force

The Royal Air Force (RAF) is the Air force, air and space force of the United Kingdom, British Overseas Territories and Crown Dependencies. It was formed towards the end of the World War I, First World War on 1 April 1918, on the merger of t ...

during the First World War

World War I or the First World War (28 July 1914 – 11 November 1918), also known as the Great War, was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War I, Allies (or Entente) and the Central Powers. Fighting to ...

. In 1920, he was made Duke of York

Duke of York is a title of nobility in the Peerage of the United Kingdom. Since the 15th century, it has, when granted, usually been given to the second son of List of English monarchs, English (later List of British monarchs, British) monarchs ...

. He married

Marriage, also called matrimony or wedlock, is a culturally and often legally recognised union between people called spouses. It establishes rights and obligations between them, as well as between them and their children (if any), and b ...

Lady Elizabeth Bowes-Lyon in 1923, and they had two daughters, Elizabeth and Margaret

Margaret is a feminine given name, which means "pearl". It is of Latin origin, via Ancient Greek and ultimately from Iranian languages, Old Iranian. It has been an English language, English name since the 11th century, and remained popular thro ...

. In the mid-1920s, he engaged speech therapist Lionel Logue

Lionel George Logue (26 February 1880 – 12 April 1953) was an Australian speech and language therapist and amateur stage actor who helped George VI, King George VI manage his Stuttering, stammer.

Early life and family

Logue was born on 26 F ...

to treat his stutter

Stuttering, also known as stammering, is a speech disorder characterized externally by involuntary repetitions and prolongations of sounds, syllables, words, or phrases as well as involuntary silent pauses called blocks in which the person who ...

, which he learned to manage to some degree. His elder brother ascended the throne as Edward VIII after their father died in 1936, but Edward abdicated later that year to marry the twice-divorced American socialite Wallis Simpson

Wallis, Duchess of Windsor (born Bessie Wallis Warfield, later Spencer and then Simpson; June 19, 1896 – April 24, 1986) was an American socialite and the wife of Prince Edward, Duke of Windsor (former King Edward VIII). Their intentio ...

. As heir presumptive

An heir presumptive is the person entitled to inherit a throne, peerage, or other hereditary honour, but whose position can be displaced by the birth of a person with a better claim to the position in question. This is in contrast to an heir app ...

to Edward VIII, Albert became king, taking the regnal name

A regnal name, regnant name, or reign name is the name used by monarchs and popes during their reigns and subsequently, historically. Since ancient times, some monarchs have chosen to use a different name from their original name when they accede ...

George VI.

In September 1939, the British Empire

The British Empire comprised the dominions, Crown colony, colonies, protectorates, League of Nations mandate, mandates, and other Dependent territory, territories ruled or administered by the United Kingdom and its predecessor states. It bega ...

and most Commonwealth countries— but not Ireland— declared war on Nazi Germany

Nazi Germany, officially known as the German Reich and later the Greater German Reich, was the German Reich, German state between 1933 and 1945, when Adolf Hitler and the Nazi Party controlled the country, transforming it into a Totalit ...

, following the invasion of Poland

The invasion of Poland, also known as the September Campaign, Polish Campaign, and Polish Defensive War of 1939 (1 September – 6 October 1939), was a joint attack on the Second Polish Republic, Republic of Poland by Nazi Germany, the Slovak R ...

. War with the Kingdom of Italy

The Kingdom of Italy (, ) was a unitary state that existed from 17 March 1861, when Victor Emmanuel II of Kingdom of Sardinia, Sardinia was proclamation of the Kingdom of Italy, proclaimed King of Italy, until 10 June 1946, when the monarchy wa ...

and the Empire of Japan

The Empire of Japan, also known as the Japanese Empire or Imperial Japan, was the Japanese nation state that existed from the Meiji Restoration on January 3, 1868, until the Constitution of Japan took effect on May 3, 1947. From Japan–Kor ...

followed in 1940 and 1941, respectively. George VI was seen as sharing the hardships of the common people and his popularity soared. Buckingham Palace

Buckingham Palace () is a royal official residence, residence in London, and the administrative headquarters of the monarch of the United Kingdom. Located in the City of Westminster, the palace is often at the centre of state occasions and r ...

was bombed during the Blitz

The Blitz (English: "flash") was a Nazi Germany, German bombing campaign against the United Kingdom, for eight months, from 7 September 1940 to 11 May 1941, during the Second World War.

Towards the end of the Battle of Britain in 1940, a co ...

while the King and Queen were there, and his younger brother the Duke of Kent

Duke of Kent is a title that has been created several times in the peerages of peerage of Great Britain, Great Britain and the peerage of the United Kingdom, United Kingdom, most recently as a Royal dukedoms in the United Kingdom, royal dukedom ...

was killed on active service. George became known as a symbol of British determination to win the war. Britain and its allies were victorious in 1945, but the British Empire declined. Ireland had largely broken away, followed by the independence of India and Pakistan in 1947. George relinquished the title of Emperor of India in June 1948 and instead adopted the new title of Head of the Commonwealth. He was beset by smoking-related health problems in the later years of his reign and died at Sandringham House

Sandringham House is a country house in the parish of Sandringham, Norfolk, England. It is one of the royal residences of Charles III, whose grandfather, George VI, and great-grandfather, George V, both died there. The house stands in a est ...

, aged 56, of a coronary thrombosis

Coronary thrombosis is defined as the formation of a blood clot inside a blood vessel of the heart. This blood clot may then restrict blood flow within the heart, leading to heart tissue damage, or a myocardial infarction, also known as a heart ...

. He was succeeded by his elder daughter, Elizabeth II.

Early life

Albert was born at

Albert was born at York Cottage

York Cottage is a house in the grounds of Sandringham House in Norfolk, England.

History

The cottage was originally called the Bachelor's Cottage, and built as an overflow residence for Sandringham House.

In 1893, it was given by the future ...

, on the Sandringham Estate in Norfolk, during the reign of his great-grandmother Queen Victoria

Victoria (Alexandrina Victoria; 24 May 1819 – 22 January 1901) was Queen of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland from 20 June 1837 until Death and state funeral of Queen Victoria, her death in January 1901. Her reign of 63 year ...

. His father was Prince George, Duke of York (later King George V

George V (George Frederick Ernest Albert; 3 June 1865 – 20 January 1936) was King of the United Kingdom and the British Dominions, and Emperor of India, from 6 May 1910 until Death and state funeral of George V, his death in 1936.

George w ...

), the second and only surviving son of the Prince and Princess of Wales (later King Edward VII

Edward VII (Albert Edward; 9 November 1841 – 6 May 1910) was King of the United Kingdom and the British Dominions, and Emperor of India, from 22 January 1901 until Death and state funeral of Edward VII, his death in 1910.

The second child ...

and Queen Alexandra

Alexandra of Denmark (Alexandra Caroline Marie Charlotte Louise Julia; 1 December 1844 – 20 November 1925) was List of British royal consorts, queen-consort of the United Kingdom and the British Dominions, and Empress of India, from 22 Januar ...

). His mother, the Duchess of York (later Queen Mary), was the eldest child and only daughter of Francis, Duke of Teck

Francis, Duke of Teck (Francis Paul Charles Louis Alexander; 28 August 1837 – 21 January 1900), known as Count Francis von Hohenstein until 1863, was an Austrian-born nobleman who married into the British royal family. His wife, Princess M ...

, and Princess Mary Adelaide, Duchess of Teck. His birthday, 14 December 1895, was the 34th anniversary of the death of his great-grandfather Albert, Prince Consort

Prince Albert of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha (Franz August Karl Albert Emanuel; 26 August 1819 – 14 December 1861) was the husband of Queen Victoria. As such, he was consort of the British monarch from their marriage on 10 February 1840 until his ...

. Uncertain of how the Prince Consort's widow, Queen Victoria, would take the news of the birth, the Prince of Wales wrote to the Duke of York that the Queen had been "rather distressed". Two days later, he wrote again: "I really think it would gratify her if you yourself proposed the name ''Albert'' to her."

The Queen was mollified by the proposal to name the new baby Albert, and wrote to the Duchess of York: "I am all impatience to see the one, born on such a sad day but rather more dear to me, especially as he will be called by that dear name which is a byword for all that is great and good." Consequently, he was baptised

Baptism (from ) is a Christians, Christian sacrament of initiation almost invariably with the use of water. It may be performed by aspersion, sprinkling or affusion, pouring water on the head, or by immersion baptism, immersing in water eit ...

"Albert Frederick Arthur George" at St Mary Magdalene Church, Sandringham on 17 February 1896. Formally he was His Highness Prince Albert of York; within the royal family

A royal family is the immediate family of monarchs and sometimes their extended family.

The term imperial family appropriately describes the family of an emperor or empress, and the term papal family describes the family of a pope, while th ...

he was known informally as "Bertie". The Duchess of Teck did not like the first name her grandson had been given, and she wrote prophetically that she hoped the last name "may supplant the less favoured one". Albert was fourth in line to the throne at birth, after his grandfather, father and elder brother, Edward

Edward is an English male name. It is derived from the Anglo-Saxon name ''Ēadweard'', composed of the elements '' ēad'' "wealth, fortunate; prosperous" and '' weard'' "guardian, protector”.

History

The name Edward was very popular in Anglo-S ...

.

Albert was ill often and was described as "easily frightened and somewhat prone to tears". His parents were generally removed from their children's day-to-day upbringing, as was the norm in aristocratic families of that era. He had a stutter

Stuttering, also known as stammering, is a speech disorder characterized externally by involuntary repetitions and prolongations of sounds, syllables, words, or phrases as well as involuntary silent pauses called blocks in which the person who ...

that lasted for many years. Although naturally left-handed

In human biology, handedness is an individual's preferential use of one hand, known as the dominant hand, due to and causing it to be stronger, faster or more dextrous. The other hand, comparatively often the weaker, less dextrous or simply l ...

, he was forced to write with his right hand, as was common practice at the time. He had chronic stomach problems as well as knock knees, for which he was forced to wear painful corrective splints.

Queen Victoria died on 22 January 1901, and the Prince of Wales succeeded her as King Edward VII. Prince Albert moved up to third in line to the throne, after his father and elder brother.

Military career and education

Beginning in 1909, Albert attended the

Beginning in 1909, Albert attended the Royal Naval College, Osborne

The Royal Naval College, Osborne, was a training college for Royal Navy officer cadets on the Osborne House estate, Isle of Wight, established in 1903 and closed in 1921.

Boys were admitted at about the age of thirteen to follow a course lasting ...

, as a naval cadet

A cadet is a student or trainee within various organisations, primarily in military contexts where individuals undergo training to become commissioned officers. However, several civilian organisations, including civil aviation groups, maritime ...

. In 1911 he came bottom of the class in the final examination, but despite this he progressed to the Royal Naval College, Dartmouth. When his grandfather Edward VII died in 1910, his father became King George V. Prince Edward became Prince of Wales, with Albert second in line to the throne.

Albert spent the first six months of 1913 on the training ship in the West Indies

The West Indies is an island subregion of the Americas, surrounded by the Atlantic Ocean, North Atlantic Ocean and the Caribbean Sea, which comprises 13 independent island country, island countries and 19 dependent territory, dependencies in thr ...

and on the east coast of Canada. He was rated as a midshipman

A midshipman is an officer of the lowest Military rank#Subordinate/student officer, rank in the Royal Navy, United States Navy, and many Commonwealth of Nations, Commonwealth navies. Commonwealth countries which use the rank include Royal Cana ...

aboard on 15 September 1913. He spent three months in the Mediterranean, but never overcame his seasickness. Three weeks after the outbreak of World War I he was medically evacuated from the ship to Aberdeen, where his appendix was removed by John Marnoch. He was mentioned in dispatches

To be mentioned in dispatches (or despatches) describes a member of the armed forces whose name appears in an official report written by a superior officer and sent to the high command, in which their gallant or meritorious action in the face of t ...

for his actions as a turret officer aboard ''Collingwood'' in the Battle of Jutland

The Battle of Jutland () was a naval battle between Britain's Royal Navy Grand Fleet, under Admiral John Jellicoe, 1st Earl Jellicoe, Sir John Jellicoe, and the Imperial German Navy's High Seas Fleet, under Vice-Admiral Reinhard Scheer, durin ...

(31 May – 1 June 1916), the great naval battle of the war. He did not see further combat, largely because of ill health caused by a duodenal ulcer

Peptic ulcer disease is when the inner part of the stomach's gastric mucosa (lining of the stomach), the first part of the small intestine, or sometimes the lower esophagus, gets damaged. An ulcer in the stomach is called a gastric ulcer, while ...

, for which he had an operation in November 1917.Bradford, pp. 55–76

In February 1918 Albert was appointed Officer in Charge of Boys at the Royal Naval Air Service

The Royal Naval Air Service (RNAS) was the air arm of the Royal Navy, under the direction of the Admiralty (United Kingdom), Admiralty's Air Department, and existed formally from 1 July 1914 to 1 April 1918, when it was merged with the British ...

's training establishment at Cranwell. With the establishment of the Royal Air Force

The Royal Air Force (RAF) is the Air force, air and space force of the United Kingdom, British Overseas Territories and Crown Dependencies. It was formed towards the end of the World War I, First World War on 1 April 1918, on the merger of t ...

Albert transferred from the Royal Navy to the Royal Air Force. He served as Officer Commanding Number 4 Squadron of the Boys' Wing at Cranwell until August 1918, before reporting for duty on the staff of the RAF's Cadet Brigade at St Leonards-on-Sea

St Leonards-on-Sea (commonly known as St Leonards) is a town and seaside resort in the borough of Hastings in East Sussex, England. It has been part of the borough since the late 19th century and lies to the west of central Hastings. The origin ...

and then at Shorncliffe. He completed a fortnight's training and took command of a squadron on the Cadet Wing. He was the first member of the British royal family to be certified as a fully qualified pilot.

Albert wanted to serve on the Continent while the war was still in progress and welcomed a posting to General Trenchard's staff in France. On 23 October, he flew across the Channel to Autigny. For the closing weeks of the war, he served on the staff of the RAF's Independent Air Force at its headquarters in Nancy, France

Nancy is the Prefectures in France, prefecture of the northeastern Departments of France, French department of Meurthe-et-Moselle. It was the capital of the Duchy of Lorraine, which was Lorraine and Barrois, annexed by France under King Louis X ...

. Following the disbanding of the Independent Air Force in November 1918, he remained on the Continent for two months as an RAF staff officer until posted back to Britain. He accompanied King Albert I of Belgium on his triumphal re-entry into Brussels on 22 November. The prince qualified as an RAF pilot on 31 July 1919 and was promoted to squadron leader

Squadron leader (Sqn Ldr or S/L) is a senior officer rank used by some air forces, with origins from the Royal Air Force. The rank is used by air forces of many countries that have historical British influence.

Squadron leader is immediatel ...

the following day.

In October 1919, Albert attended Trinity College, Cambridge

Trinity College is a Colleges of the University of Cambridge, constituent college of the University of Cambridge. Founded in 1546 by King Henry VIII, Trinity is one of the largest Cambridge colleges, with the largest financial endowment of any ...

, where he studied history, economics and civics for a year, with the historian R. V. Laurence as his "official mentor". On 4 June 1920 his father created him Duke of York

Duke of York is a title of nobility in the Peerage of the United Kingdom. Since the 15th century, it has, when granted, usually been given to the second son of List of English monarchs, English (later List of British monarchs, British) monarchs ...

, Earl of Inverness

The title of Earl of Inverness (Scottish Gaelic: Iarla Inbhir Nis) is a title of nobility in the Peerage of the United Kingdom. It was first created in 1718 in the Jacobite Peerage of Scotland, together with the titles Viscount of Innerpaphr ...

and Baron Killarney. He began to take on more royal duties. He represented his father and toured coal mines, factories, and railyards. Through such visits he acquired the nickname of the "Industrial Prince". His stutter, and his embarrassment over it, together with a tendency to shyness, caused him to appear less confident in public than his older brother, Edward. However, he was physically active and enjoyed playing tennis. He played at Wimbledon

Wimbledon most often refers to:

* Wimbledon, London, a district of southwest London

* Wimbledon Championships, the oldest tennis tournament in the world and one of the four Grand Slam championships

Wimbledon may also refer to:

Places London

* W ...

in the Men's Doubles with Louis Greig

Group Captain Sir Louis Leisler Greig, Order of the British Empire, KBE Royal Victorian Order, CVO (17 November 1880 – 1 March 1953) was a Scottish people, Scottish naval surgeon, rugby union, rugby player, courtier and a friend of King Georg ...

in 1926, losing in the first round. He developed an interest in working conditions, and was president of the Industrial Welfare Society. His series of annual summer camps for boys between 1921 and 1939 brought together boys from different social backgrounds.

Marriage

In a time when royalty were expected to marry fellow royalty, it was unusual that Albert had a great deal of freedom in choosing a prospective wife. The King brought his son's infatuation with the already-married Australian socialite Lady Loughborough to an end in April 1920 by persuading him to stop seeing her, with the promise of the dukedom of York. That year, Albert met for the first time since childhood Lady Elizabeth Bowes-Lyon, the youngest daughter of theEarl

Earl () is a rank of the nobility in the United Kingdom. In modern Britain, an earl is a member of the Peerages in the United Kingdom, peerage, ranking below a marquess and above a viscount. A feminine form of ''earl'' never developed; instead, ...

and Countess of Strathmore. He became determined to marry her. Elizabeth rejected his proposal twice, in 1921 and 1922, reportedly because she was reluctant to make the sacrifices necessary to become a member of the royal family. In the words of Lady Strathmore, Albert would be "made or marred" by his choice of wife. After a protracted courtship, Elizabeth agreed to marry him.

Albert and Elizabeth were married on 26 April 1923 in Westminster Abbey

Westminster Abbey, formally titled the Collegiate Church of Saint Peter at Westminster, is an Anglican church in the City of Westminster, London, England. Since 1066, it has been the location of the coronations of 40 English and British m ...

. Albert's marriage to someone not of royal birth was considered a modernising gesture. The newly formed British Broadcasting Company

The British Broadcasting Company Limited (BBC) was a short-lived British commercial broadcasting company formed on 18 October 1922 by British and American electrical companies doing business in the United Kingdom. Licensed by the British Gener ...

wished to record and broadcast the event on radio, but the Abbey Chapter vetoed the idea (although the Dean, Herbert Edward Ryle, was in favour).

From December 1924 to April 1925, the Duke and Duchess toured

From December 1924 to April 1925, the Duke and Duchess toured Kenya

Kenya, officially the Republic of Kenya, is a country located in East Africa. With an estimated population of more than 52.4 million as of mid-2024, Kenya is the 27th-most-populous country in the world and the 7th most populous in Africa. ...

, Uganda

Uganda, officially the Republic of Uganda, is a landlocked country in East Africa. It is bordered to the east by Kenya, to the north by South Sudan, to the west by the Democratic Republic of the Congo, to the south-west by Rwanda, and to the ...

, and the Sudan

Sudan, officially the Republic of the Sudan, is a country in Northeast Africa. It borders the Central African Republic to the southwest, Chad to the west, Libya to the northwest, Egypt to the north, the Red Sea to the east, Eritrea and Ethiopi ...

, travelling via the Suez Canal

The Suez Canal (; , ') is an artificial sea-level waterway in Egypt, Indo-Mediterranean, connecting the Mediterranean Sea to the Red Sea through the Isthmus of Suez and dividing Africa and Asia (and by extension, the Sinai Peninsula from the rest ...

and Aden

Aden () is a port city located in Yemen in the southern part of the Arabian peninsula, on the north coast of the Gulf of Aden, positioned near the eastern approach to the Red Sea. It is situated approximately 170 km (110 mi) east of ...

. During the trip, they both went big-game hunting

Big-game hunting is the hunting of large game animals for trophies, taxidermy, meat, and commercially valuable animal by-products (such as horns, antlers, tusks, bones, fur, body fat, or special organs). The term is often associated with t ...

.

Because of his stutter, Albert dreaded public speaking. After his closing speech at the British Empire Exhibition

The British Empire Exhibition was a colonial exhibition held at Wembley Park, London England from 23 April to 1 November 1924 and from 9 May to 31 October 1925.

Background

In 1920 the Government of the United Kingdom, British Government decide ...

at Wembley

Wembley () is a large suburbIn British English, "suburb" often refers to the secondary urban centres of a city. Wembley is not a suburb in the American sense, i.e. a single-family residential area outside of the city itself. in the London Borou ...

on 31 October 1925, one which was an ordeal for both him and his listeners, he began to see Lionel Logue

Lionel George Logue (26 February 1880 – 12 April 1953) was an Australian speech and language therapist and amateur stage actor who helped George VI, King George VI manage his Stuttering, stammer.

Early life and family

Logue was born on 26 F ...

, an Australian-born speech therapist. The Duke and Logue practised breathing exercises, and the Duchess rehearsed with him patiently. Subsequently, he was able to speak with less hesitation. With his delivery improved, Albert opened the new Parliament House in Canberra

Canberra ( ; ) is the capital city of Australia. Founded following the Federation of Australia, federation of the colonies of Australia as the seat of government for the new nation, it is Australia's list of cities in Australia, largest in ...

, Australia, during a tour of the empire with his wife in 1927. Their journey by sea to Australia, New Zealand and Fiji took them via Jamaica, where Albert played doubles tennis partnered with a black man, Bertrand Clark, which was unusual at the time and taken locally as a display of equality between races.

The Duke and Duchess had two children, Elizabeth (called "Lilibet" by the family, later Elizabeth II) in 1926 and Margaret

Margaret is a feminine given name, which means "pearl". It is of Latin origin, via Ancient Greek and ultimately from Iranian languages, Old Iranian. It has been an English language, English name since the 11th century, and remained popular thro ...

in 1930. The family lived at White Lodge, Richmond Park, and then at 145 Piccadilly

Piccadilly () is a road in the City of Westminster, London, England, to the south of Mayfair, between Hyde Park Corner in the west and Piccadilly Circus in the east. It is part of the A4 road (England), A4 road that connects central London to ...

, rather than one of the royal palaces. In 1931, the Canadian prime minister, R. B. Bennett, considered Albert for Governor General of Canada

The governor general of Canada () is the federal representative of the . The monarch of Canada is also sovereign and head of state of 14 other Commonwealth realms and resides in the United Kingdom. The monarch, on the Advice (constitutional la ...

—a proposal that King George V rejected on the advice of the Secretary of State for Dominion Affairs

The position of secretary of state for dominion affairs was a secretary of state in the Government of the United Kingdom, responsible for British relations with the Empire’s dominions – Canada, Australia, New Zealand, South Africa, Newfoundl ...

, J. H. Thomas

James Henry Thomas (3 October 1874 – 21 January 1949) was a Welsh people, Welsh trade unionist and politician. He was involved in a British political scandals, political scandal involving budget leaks.

Early career and trade union activiti ...

.

Reign

Reluctant king

King George V had severe reservations about Prince Edward, saying "After I am dead, the boy will ruin himself in twelve months" and "I pray God that my eldest son will never marry and that nothing will come between Bertie and Lilibet and the throne." On 20 January 1936, George V died and Edward ascended the throne as King Edward VIII. In the Vigil of the Princes, Prince Albert and his three brothers (the new king,Prince Henry, Duke of Gloucester

Prince Henry, Duke of Gloucester (Henry William Frederick Albert; 31 March 1900 – 10 June 1974) was a member of the British royal family. He was the third son of King George V and Mary of Teck, Queen Mary, and was a younger brother of kings E ...

, and Prince George, Duke of Kent

Prince George, Duke of Kent (George Edward Alexander Edmund; 20 December 1902 – 25 August 1942) was a member of the British royal family, the fourth son of King George V and Queen Mary. He was a younger brother of kings Edward VIII and George ...

) took a shift standing guard over their father's body as it lay in state, in a closed casket, in Westminster Hall

Westminster Hall is a medieval great hall which is part of the Palace of Westminster in London, England. It was erected in 1097 for William II (William Rufus), at which point it was the largest hall in Europe. The building has had various functio ...

.

As Edward was unmarried and had no children, Albert was the heir presumptive

An heir presumptive is the person entitled to inherit a throne, peerage, or other hereditary honour, but whose position can be displaced by the birth of a person with a better claim to the position in question. This is in contrast to an heir app ...

to the throne. Less than a year later, on 11 December 1936, Edward abdicated in order to marry Wallis Simpson

Wallis, Duchess of Windsor (born Bessie Wallis Warfield, later Spencer and then Simpson; June 19, 1896 – April 24, 1986) was an American socialite and the wife of Prince Edward, Duke of Windsor (former King Edward VIII). Their intentio ...

, who was divorced from her first husband and divorcing her second. Edward had been advised by British prime minister Stanley Baldwin

Stanley Baldwin, 1st Earl Baldwin of Bewdley (3 August 186714 December 1947), was a British statesman and Conservative politician who was prominent in the political leadership of the United Kingdom between the world wars. He was prime ministe ...

that he could not remain king and marry a divorced woman with two living ex-husbands. He abdicated and Albert, though he had been reluctant to accept the throne, became king. The day before the abdication, Albert went to London to see his mother, Queen Mary. He wrote in his diary, "When I told her what had happened, I broke down and sobbed like a child."

On the day of Edward's abdication, the Oireachtas

The Oireachtas ( ; ), sometimes referred to as Oireachtas Éireann, is the Bicameralism, bicameral parliament of Republic of Ireland, Ireland. The Oireachtas consists of the president of Ireland and the two houses of the Oireachtas (): a house ...

, the parliament of the Irish Free State

The Irish Free State (6 December 192229 December 1937), also known by its Irish-language, Irish name ( , ), was a State (polity), state established in December 1922 under the Anglo-Irish Treaty of December 1921. The treaty ended the three-ye ...

, removed all direct mention of the monarch from the Irish constitution

The Constitution of Ireland (, ) is the fundamental law of Ireland. It asserts the national sovereignty of the Irish people. It guarantees certain fundamental rights, along with a popularly elected non-executive president, a bicameral parliam ...

. The next day, it passed the External Relations Act, which gave the monarch limited authority (strictly on the advice of the government) to appoint diplomatic representatives for Ireland and to be involved in the making of foreign treaties. The two acts made the Irish Free State a republic in essence without removing its links to the Commonwealth.

Across Britain, gossip spread that Albert was physically and psychologically incapable of being king. No evidence has been found to support the contemporaneous rumour that the government considered bypassing him, his children and his brother Prince Henry, in favour of their younger brother Prince George, Duke of Kent. This seems to have been suggested on the grounds that Prince George was at that time the only brother with a son.

Early reign

Albert assumed the

Albert assumed the regnal name

A regnal name, regnant name, or reign name is the name used by monarchs and popes during their reigns and subsequently, historically. Since ancient times, some monarchs have chosen to use a different name from their original name when they accede ...

"George VI" to emphasise continuity with his father and restore confidence in the monarchy. The beginning of George VI's reign was taken up by questions surrounding his predecessor and brother, whose titles, style and position were uncertain. He had been introduced as "His Royal Highness Prince Edward" for the abdication broadcast, but George VI felt that by abdicating and renouncing the succession, Edward had lost the right to bear royal titles, including "Royal Highness". In settling the issue, George's first act as king was to confer upon Edward the title "Duke of Windsor

Duke of Windsor was a title in the Peerage of the United Kingdom. It was created on 8 March 1937 for the former monarch Edward VIII, following his Abdication of Edward VIII, abdication on 11 December 1936. The Duchy, dukedom takes its name from ...

" with the style "Royal Highness", but the letters patent

Letters patent (plurale tantum, plural form for singular and plural) are a type of legal instrument in the form of a published written order issued by a monarch, President (government title), president or other head of state, generally granti ...

creating the dukedom prevented any wife or children from bearing royal styles. George VI was forced to buy from Edward the royal residences of Balmoral Castle

Balmoral Castle () is a large estate house in Aberdeenshire, Scotland, and a residence of the British royal family. It is near the village of Crathie, west of Ballater and west of Aberdeen.

The estate and its original castle were bought ...

and Sandringham House

Sandringham House is a country house in the parish of Sandringham, Norfolk, England. It is one of the royal residences of Charles III, whose grandfather, George VI, and great-grandfather, George V, both died there. The house stands in a est ...

, as these were private properties and did not pass to him automatically. Three days after his accession, on his 41st birthday, he invested his wife, the new queen consort

A queen consort is the wife of a reigning king, and usually shares her spouse's social Imperial, royal and noble ranks, rank and status. She holds the feminine equivalent of the king's monarchical titles and may be crowned and anointed, but hi ...

, with the Order of the Garter

The Most Noble Order of the Garter is an order of chivalry founded by Edward III of England in 1348. The most senior order of knighthood in the Orders, decorations, and medals of the United Kingdom, British honours system, it is outranked in ...

.

George VI's coronation at Westminster Abbey took place on 12 May 1937, the date previously intended for Edward's coronation. In a break with tradition, Queen Mary attended the ceremony in a show of support for her son. There was no Durbar held in Delhi for George VI, as had occurred for his father, as the cost would have been a burden to the

George VI's coronation at Westminster Abbey took place on 12 May 1937, the date previously intended for Edward's coronation. In a break with tradition, Queen Mary attended the ceremony in a show of support for her son. There was no Durbar held in Delhi for George VI, as had occurred for his father, as the cost would have been a burden to the Government of India

The Government of India (ISO 15919, ISO: Bhārata Sarakāra, legally the Union Government or Union of India or the Central Government) is the national authority of the Republic of India, located in South Asia, consisting of States and union t ...

. Rising Indian nationalism

Indian nationalism is an instance of civic nationalism. It is inclusive of all of the people of India, Composite nationalism (India), despite their Demographics of India, diverse ethnic, linguistic and religious backgrounds. Indian national ...

made the welcome that the royal party would have received likely to be muted at best, and a prolonged absence from Britain would have been undesirable in the tense period before the Second World War. Two overseas tours were undertaken, to France and to North America, both of which promised greater strategic advantages in the event of war.

The growing likelihood of war in Europe dominated the early reign of George VI. The King was constitutionally bound to support British prime minister Neville Chamberlain

Arthur Neville Chamberlain (; 18 March 18699 November 1940) was a British politician who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from May 1937 to May 1940 and Leader of the Conservative Party (UK), Leader of the Conservative Party from ...

's appeasement

Appeasement, in an International relations, international context, is a diplomacy, diplomatic negotiation policy of making political, material, or territorial concessions to an aggressive power (international relations), power with intention t ...

of Hitler

Adolf Hitler (20 April 1889 – 30 April 1945) was an Austrian-born German politician who was the dictator of Nazi Germany from 1933 until Death of Adolf Hitler, his suicide in 1945. Adolf Hitler's rise to power, He rose to power as the lea ...

. When the King and Queen greeted Chamberlain on his return from negotiating the Munich Agreement

The Munich Agreement was reached in Munich on 30 September 1938, by Nazi Germany, the United Kingdom, the French Third Republic, French Republic, and the Kingdom of Italy. The agreement provided for the Occupation of Czechoslovakia (1938–194 ...

in 1938, they invited him to appear on the balcony of Buckingham Palace

Buckingham Palace () is a royal official residence, residence in London, and the administrative headquarters of the monarch of the United Kingdom. Located in the City of Westminster, the palace is often at the centre of state occasions and r ...

with them. This public association of the monarchy with a politician was exceptional, as balcony appearances were traditionally restricted to the royal family. While broadly popular among the general public, Chamberlain's policy towards Hitler was the subject of some opposition in the House of Commons

The House of Commons is the name for the elected lower house of the Bicameralism, bicameral parliaments of the United Kingdom and Canada. In both of these countries, the Commons holds much more legislative power than the nominally upper house of ...

, which led historian and politician John Grigg to describe George's behaviour in associating himself so prominently with a politician as "the most unconstitutional act by a British sovereign in the present century".

In May and June 1939, the King and Queen toured Canada and the United States; it was the first visit of a reigning British monarch to North America, although George had been to Canada prior to his accession. From

In May and June 1939, the King and Queen toured Canada and the United States; it was the first visit of a reigning British monarch to North America, although George had been to Canada prior to his accession. From Ottawa

Ottawa is the capital city of Canada. It is located in the southern Ontario, southern portion of the province of Ontario, at the confluence of the Ottawa River and the Rideau River. Ottawa borders Gatineau, Gatineau, Quebec, and forms the cor ...

, George and Elizabeth were accompanied by Canadian prime minister Mackenzie King

William Lyon Mackenzie King (December 17, 1874 – July 22, 1950) was a Canadian statesman and politician who was the tenth prime minister of Canada for three non-consecutive terms from 1921 to 1926, 1926 to 1930, and 1935 to 1948. A Liberal ...

, to present themselves in North America as King and Queen of Canada. Both Mackenzie King and the Canadian governor general, Lord Tweedsmuir

John Buchan, 1st Baron Tweedsmuir (; 26 August 1875 – 11 February 1940) was a Scottish novelist, historian, British Army officer, and Unionist Party (Scotland), Unionist politician who served as Governor General of Canada, the List of governo ...

, hoped that George's presence in Canada would demonstrate the principles of the Statute of Westminster 1931

The Statute of Westminster 1931 is an act of the Parliament of the United Kingdom that significantly increased the autonomy of the Dominions of the British Commonwealth.

Passed on 11 December 1931, the statute increased the sovereignty of t ...

, which gave full sovereignty to the British Dominions

A dominion was any of several largely self-governance, self-governing countries of the British Empire, once known collectively as the ''British Commonwealth of Nations''. Progressing from colonies, their degrees of self-governing colony, colon ...

. On 19 May, George personally accepted and approved the letter of credence

A letter of credence (, ) is a formal Diplomatic correspondence, diplomatic letter that designates a diplomat as ambassador to another sovereign state. Commonly known as diplomatic credentials, the letter is addressed from one head of state to an ...

of the new U.S. ambassador to Canada, Daniel Calhoun Roper; gave royal assent

Royal assent is the method by which a monarch formally approves an act of the legislature, either directly or through an official acting on the monarch's behalf. In some jurisdictions, royal assent is equivalent to promulgation, while in othe ...

to nine parliamentary bills; and ratified two international treaties with the Great Seal of Canada

The Great Seal of Canada () is an official great seal used for certifying the authenticity of important state documents issued in the name of the Canadian monarch. As a symbol of the Crown's authority, it represents the constitutional power besto ...

. The official royal tour historian, Gustave Lanctot, wrote "the Statute of Westminster had assumed full reality" and George gave a speech emphasising "the free and equal association of the nations of the Commonwealth".

The trip was intended to soften the strong isolationist tendencies among the North American public with regard to the developing tensions in Europe. Although the aim of the tour was mainly political, to shore up Atlantic support for the United Kingdom in any future war, the King and Queen were enthusiastically received by the public. The fear that George would be compared unfavourably to his predecessor was dispelled. They visited the 1939 New York World's Fair

The 1939 New York World's Fair (also known as the 1939–1940 New York World's Fair) was an world's fair, international exposition at Flushing Meadows–Corona Park in Queens, New York City, New York, United States. The fair included exhibitio ...

and stayed with President Franklin D. Roosevelt

Franklin Delano Roosevelt (January 30, 1882April 12, 1945), also known as FDR, was the 32nd president of the United States, serving from 1933 until his death in 1945. He is the longest-serving U.S. president, and the only one to have served ...

at the White House

The White House is the official residence and workplace of the president of the United States. Located at 1600 Pennsylvania Avenue Northwest (Washington, D.C.), NW in Washington, D.C., it has served as the residence of every U.S. president ...

and at his private estate at Hyde Park, New York

Hyde Park is a town in Dutchess County, New York, United States, bordering the Hudson River north of Poughkeepsie. Within the town are the hamlets of Hyde Park, East Park, Staatsburg, and Haviland. Hyde Park is known as the hometown of Fra ...

. A strong bond of friendship was forged between Roosevelt and the royal couple during the tour, which had major significance in the relations between the United States and the United Kingdom through the ensuing war years.

Second World War

Following theGerman invasion of Poland

The invasion of Poland, also known as the September Campaign, Polish Campaign, and Polish Defensive War of 1939 (1 September – 6 October 1939), was a joint attack on the Second Polish Republic, Republic of Poland by Nazi Germany, the Slovak R ...

in September 1939, the United Kingdom and the self-governing Dominions other than Ireland declared war on Nazi Germany

Nazi Germany, officially known as the German Reich and later the Greater German Reich, was the German Reich, German state between 1933 and 1945, when Adolf Hitler and the Nazi Party controlled the country, transforming it into a Totalit ...

. The King and Queen resolved to stay in London, despite German bombing raids. They officially stayed in Buckingham Palace throughout the war, although they usually spent nights at Windsor Castle

Windsor Castle is a List of British royal residences, royal residence at Windsor, Berkshire, Windsor in the English county of Berkshire, about west of central London. It is strongly associated with the Kingdom of England, English and succee ...

. The first night of the Blitz on London, on 7 September 1940, killed about one thousand civilians, mostly in the East End. On 13 September, the couple narrowly avoided death when two German bombs exploded in a courtyard at Buckingham Palace while they were there. In defiance, the Queen declared: "I am glad we have been bombed. It makes me feel we can look the East End in the face." The royal family were portrayed as sharing the same dangers and deprivations as the rest of the country. They were subject to British rationing restrictions, and the U.S. first lady Eleanor Roosevelt

Anna Eleanor Roosevelt ( ; October 11, 1884November 7, 1962) was an American political figure, diplomat, and activist. She was the longest-serving First Lady of the United States, first lady of the United States, during her husband Franklin D ...

remarked on the rationed food served and the limited bathwater that was permitted during a stay at the unheated and boarded-up Palace. In August 1942, the King's brother, the Duke of Kent, was killed on active service.

In 1940,

In 1940, Winston Churchill

Sir Winston Leonard Spencer Churchill (30 November 1874 – 24 January 1965) was a British statesman, military officer, and writer who was Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 1940 to 1945 (Winston Churchill in the Second World War, ...

replaced Neville Chamberlain as prime minister, though personally George would have preferred to appoint Lord Halifax

Edward Frederick Lindley Wood, 1st Earl of Halifax (16 April 1881 – 23 December 1959), known as the Lord Irwin from 1925 until 1934 and the Viscount Halifax from 1934 until 1944, was a British Conservative politician of the 1930s. He h ...

. After the King's initial dismay over Churchill's appointment of Lord Beaverbrook

William Maxwell Aitken, 1st Baron Beaverbrook (25 May 1879 – 9 June 1964), was a Canadian-British newspaper publisher and backstage politician who was an influential figure in British media and politics of the first half of the 20th century ...

to the Cabinet, he and Churchill developed "the closest personal relationship in modern British history between a monarch and a Prime Minister". Every Tuesday for four and a half years from September 1940, the two men met privately for lunch to discuss the war in secret and with frankness. George related much of what the two discussed in his diary, which is the only extant first-hand account of these conversations.

Throughout the war, George and Elizabeth provided morale-boosting visits throughout the United Kingdom, visiting bomb sites, munitions factories, and troops. George visited military forces abroad in France in December 1939, North Africa and Malta

Malta, officially the Republic of Malta, is an island country in Southern Europe located in the Mediterranean Sea, between Sicily and North Africa. It consists of an archipelago south of Italy, east of Tunisia, and north of Libya. The two ...

in June 1943, Normandy

Normandy (; or ) is a geographical and cultural region in northwestern Europe, roughly coextensive with the historical Duchy of Normandy.

Normandy comprises Normandy (administrative region), mainland Normandy (a part of France) and insular N ...

in June 1944, southern Italy in July 1944, and the Low Countries in October 1944. Their high public profile and apparently indefatigable determination secured their place as symbols of national resistance. At a social function in 1944, the Chief of the Imperial General Staff

Chief of the General Staff (CGS) has been the title of the professional head of the British Army since 1964. The CGS is a member of both the Chiefs of Staff Committee and the Army Board; he is also the Chair of the Executive Committee of the A ...

, Field Marshal

Field marshal (or field-marshal, abbreviated as FM) is the most senior military rank, senior to the general officer ranks. Usually, it is the highest rank in an army (in countries without the rank of Generalissimo), and as such, few persons a ...

Alan Brooke

Field Marshal Alan Francis Brooke, 1st Viscount Alanbrooke (23 July 1883 – 17 June 1963), was a senior officer of the British Army. He was Chief of the Imperial General Staff (CIGS), the professional head of the British Army, during the Secon ...

, revealed that every time he met Field Marshal Bernard Montgomery

Field Marshal Bernard Law Montgomery, 1st Viscount Montgomery of Alamein (; 17 November 1887 – 24 March 1976), nicknamed "Monty", was a senior British Army officer who served in the First World War, the Irish War of Independence and the ...

, he thought Montgomery was after his job. George replied: "You should worry, when I meet him, I always think he's after mine!"

In 1945, crowds shouted "We want the King!" in front of Buckingham Palace during the Victory in Europe Day

Victory in Europe Day is the day celebrating the formal acceptance by the Allies of World War II of Germany's unconditional surrender of its armed forces on Tuesday, 8 May 1945; it marked the official surrender of all German military operations ...

celebrations. In an echo of Chamberlain's appearance, the King invited Churchill to appear with the royal family on the balcony to public acclaim. In January 1946, George addressed the United Nations

The United Nations (UN) is the Earth, global intergovernmental organization established by the signing of the Charter of the United Nations, UN Charter on 26 June 1945 with the stated purpose of maintaining international peace and internationa ...

at its first assembly, which was held in London, and reaffirmed "our faith in the equal rights of men and women and of nations great and small".

Empire to Commonwealth

George VI's reign saw the acceleration of the dissolution of the

George VI's reign saw the acceleration of the dissolution of the British Empire

The British Empire comprised the dominions, Crown colony, colonies, protectorates, League of Nations mandate, mandates, and other Dependent territory, territories ruled or administered by the United Kingdom and its predecessor states. It bega ...

. The Statute of Westminster 1931 had already acknowledged the evolution of the Dominions into separate sovereign

''Sovereign'' is a title that can be applied to the highest leader in various categories. The word is borrowed from Old French , which is ultimately derived from the Latin">-4; we might wonder whether there's a point at which it's appropriate to ...

states. The process of transformation from an empire to a voluntary association of independent states, known as the Commonwealth

A commonwealth is a traditional English term for a political community founded for the common good. The noun "commonwealth", meaning "public welfare, general good or advantage", dates from the 15th century. Originally a phrase (the common-wealth ...

, gathered pace after the Second World War. During the ministry of Clement Attlee

Clement Richard Attlee, 1st Earl Attlee (3 January 18838 October 1967) was a British statesman who was Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 1945 to 1951 and Leader of the Labour Party (UK), Leader of the Labour Party from 1935 to 1955. At ...

, British India

The provinces of India, earlier presidencies of British India and still earlier, presidency towns, were the administrative divisions of British governance in South Asia. Collectively, they have been called British India. In one form or another ...

became the two independent Dominions of India

India, officially the Republic of India, is a country in South Asia. It is the List of countries and dependencies by area, seventh-largest country by area; the List of countries by population (United Nations), most populous country since ...

and Pakistan

Pakistan, officially the Islamic Republic of Pakistan, is a country in South Asia. It is the List of countries and dependencies by population, fifth-most populous country, with a population of over 241.5 million, having the Islam by country# ...

in August 1947. George relinquished the title of Emperor of India

Emperor (or Empress) of India was a title used by British monarchs from 1 May 1876 (with the Royal Titles Act 1876) to 22 June 1948 Royal Proclamation of 22 June 1948, made in accordance with thIndian Independence Act 1947, 10 & 11 GEO. 6. CH ...

, and became King of India and King of Pakistan instead. In late April 1949, the Commonwealth leaders issued the London Declaration

The London Declaration was a declaration issued by the 1949 Commonwealth Prime Ministers' Conference on the issue of India's continued membership of the Commonwealth of Nations, an association of independent states formerly part of the British ...

, which laid the foundation of the modern Commonwealth and recognised George as Head of the Commonwealth

The Head of the Commonwealth is the ceremonial leader who symbolises "the free association of independent member nations" of the Commonwealth of Nations, an intergovernmental organisation that currently comprises 56 sovereign states. There is ...

. In January 1950, he ceased to be King of India when it became a republic. He remained King of Pakistan until his death. Other countries left the Commonwealth, such as Burma

Myanmar, officially the Republic of the Union of Myanmar; and also referred to as Burma (the official English name until 1989), is a country in northwest Southeast Asia. It is the largest country by area in Mainland Southeast Asia and ha ...

in January 1948, Palestine

Palestine, officially the State of Palestine, is a country in West Asia. Recognized by International recognition of Palestine, 147 of the UN's 193 member states, it encompasses the Israeli-occupied West Bank, including East Jerusalem, and th ...

(divided between Israel and the Arab states) in May 1948 and the Republic of Ireland in 1949.

In 1947, George and his family toured southern Africa. The prime minister of the Union of South Africa

The Union of South Africa (; , ) was the historical predecessor to the present-day South Africa, Republic of South Africa. It came into existence on 31 May 1910 with the unification of the British Cape Colony, Cape, Colony of Natal, Natal, Tra ...

, Jan Smuts

Field Marshal Jan Christian Smuts, (baptismal name Jan Christiaan Smuts, 24 May 1870 11 September 1950) was a South African statesman, military leader and philosopher. In addition to holding various military and cabinet posts, he served as P ...

, was facing an election and hoped to make political capital out of the visit. George was appalled, however, when instructed by the South African government to shake hands only with whites, and referred to his South African bodyguards as "the Gestapo

The (, ), Syllabic abbreviation, abbreviated Gestapo (), was the official secret police of Nazi Germany and in German-occupied Europe.

The force was created by Hermann Göring in 1933 by combining the various political police agencies of F ...

". Despite the tour, Smuts lost the election the following year, and the new government instituted a strict policy of racial segregation.

Illness and death

The stress of the war had taken its toll on George's health, made worse by his heavysmoking

Smoking is a practice in which a substance is combusted, and the resulting smoke is typically inhaled to be tasted and absorbed into the bloodstream of a person. Most commonly, the substance used is the dried leaves of the tobacco plant, whi ...

, and subsequent development of lung cancer

Lung cancer, also known as lung carcinoma, is a malignant tumor that begins in the lung. Lung cancer is caused by genetic damage to the DNA of cells in the airways, often caused by cigarette smoking or inhaling damaging chemicals. Damaged ...

among other ailments, including arteriosclerosis

Arteriosclerosis, literally meaning "hardening of the arteries", is an umbrella term for a vascular disorder characterized by abnormal thickening, hardening, and loss of elasticity of the walls of arteries; this process gradually restricts th ...

and Buerger's disease. A planned tour of Australia and New Zealand was postponed after George developed an arterial blockage in his right leg, which threatened the loss of the leg and was treated with a right lumbar sympathectomy in March 1949. His elder daughter and heir presumptive, Elizabeth, took on more royal duties as her father's health deteriorated. The delayed tour was re-organised, with Princess Elizabeth and her husband, Philip, Duke of Edinburgh

Prince Philip, Duke of Edinburgh (born Prince Philip of Greece and Denmark, later Philip Mountbatten; 10 June 19219 April 2021), was the husband of Queen Elizabeth II. As such, he was the consort of the British monarch from ...

, taking the place of the King and Queen.

George was well enough to open the Festival of Britain in May 1951, but on 4 June it was announced that he would need immediate and complete rest for the next four weeks, despite the arrival of Haakon VII of Norway the following afternoon for an official visit. On 23 September 1951, his left lung was removed in a surgical operation performed by Clement Price Thomas after a malignant tumour was found. In October 1951, Elizabeth and Philip went on a month-long tour of Canada; the trip had been delayed for a week due to George's illness. At the State Opening of Parliament

The State Opening of Parliament is a ceremonial event which formally marks the beginning of each Legislative session, session of the Parliament of the United Kingdom. At its core is His or Her Majesty's "Speech from the throne, gracious speech ...

in November, the Lord Chancellor

The Lord Chancellor, formally titled Lord High Chancellor of Great Britain, is a senior minister of the Crown within the Government of the United Kingdom. The lord chancellor is the minister of justice for England and Wales and the highest-ra ...

, Lord Simonds

Gavin Turnbull Simonds, 1st Viscount Simonds, (28 November 1881 – 28 June 1971) was a British judge, politician and Lord High Chancellor of Great Britain.

Background and education

Simonds was born in Reading, Berkshire, the son of Louis DeLu ...

, read the King's speech from the throne

A speech from the throne, or throne speech, is an event in certain monarchies in which the reigning sovereign, or their representative, reads a prepared speech to members of the nation's legislature when a Legislative session, session is opened. ...

. The King's Christmas broadcast of 1951 was recorded in sections, and then edited together.

On 31 January 1952, despite advice from those close to him, George went to London Airport to see Elizabeth and Philip off on their tour to Australia via Kenya. It was his last public appearance. Six days later, at 07:30 GMT on the morning of 6 February, he was found dead in bed at Sandringham House in Norfolk. He had died in the night from a coronary thrombosis

Coronary thrombosis is defined as the formation of a blood clot inside a blood vessel of the heart. This blood clot may then restrict blood flow within the heart, leading to heart tissue damage, or a myocardial infarction, also known as a heart ...

at the age of 56. His daughter flew back to Britain from Kenya as Queen Elizabeth II.

From 9 February George's coffin rested in St Mary Magdalene Church, Sandringham, before lying in state

Lying in state is the tradition in which the body of a deceased official, such as a head of state, is placed in a state building, either outside or inside a coffin, to allow the public to pay their respects. It traditionally takes place in a ...

at Westminster Hall from 11 February. His funeral took place at St George's Chapel, Windsor Castle

St George's Chapel, formally titled The King's Free Chapel of the College of St George, Windsor Castle, at Windsor Castle in England is a castle chapel built in the late-medieval Perpendicular Gothic style. It is a Royal peculiar, Royal Peculia ...

, on 15 February. He was interred initially in the Royal Vault until he was transferred to the King George VI Memorial Chapel

The King George VI Memorial Chapel is part of St George's Chapel at Windsor Castle in England. The chapel was commissioned by Elizabeth II in 1962 as a burial place for her father, George VI, and was completed in 1969. It contains the final re ...

inside St George's on 26 March 1969. In 2002, fifty years after his death, the remains of his widow, Queen Elizabeth The Queen Mother, and the ashes of his younger daughter, Princess Margaret, who both died that year, were interred in the chapel alongside him. In 2022, the remains of Queen Elizabeth II and her husband, Prince Philip, were also interred in the chapel.

Legacy

In the words of Labour Member of Parliament (MP) George Hardie, the abdication crisis of 1936 did "more for republicanism than fifty years of propaganda". George VI wrote to his brother Edward that in the aftermath of the abdication he had reluctantly assumed "a rocking throne" and tried "to make it steady again". He became king at a point when public faith in the monarchy was at a low ebb. During his reign, his people endured the hardships of war, and imperial power was eroded. However, as a dutiful family man and by showing personal courage, he succeeded in restoring the popularity of the monarchy.

The

In the words of Labour Member of Parliament (MP) George Hardie, the abdication crisis of 1936 did "more for republicanism than fifty years of propaganda". George VI wrote to his brother Edward that in the aftermath of the abdication he had reluctantly assumed "a rocking throne" and tried "to make it steady again". He became king at a point when public faith in the monarchy was at a low ebb. During his reign, his people endured the hardships of war, and imperial power was eroded. However, as a dutiful family man and by showing personal courage, he succeeded in restoring the popularity of the monarchy.

The George Cross

The George Cross (GC) is the highest award bestowed by the British government for non-operational Courage, gallantry or gallantry not in the presence of an enemy. In the British honours system, the George Cross, since its introduction in 1940, ...

and the George Medal

The George Medal (GM), instituted on 24 September 1940 by King George VI,''British Gallantry Medals'' (Abbott and Tamplin), p. 138 is a decoration of the United Kingdom and Commonwealth of Nations, Commonwealth, awarded for gallantry, typically ...

were founded at the King's suggestion during the Second World War to recognise acts of exceptional civilian bravery. He bestowed the George Cross on the entire " island fortress of Malta" in 1943. He was posthumously awarded the Order of Liberation

The Order of Liberation (, ) is a French Order which was awarded to heroes of the Liberation of France during World War II. It is a worn by recipients only before the ''Légion d’Honneur'' (Legion of Honour). In the official portrait of G ...

by the French government in 1960, one of only two people (the other being Churchill in 1958) to be awarded the medal after 1946.

Colin Firth

Colin Andrew Firth (born 10 September 1960) is an English actor and producer. He is the recipient of List of awards and nominations received by Colin Firth, several accolades, including an Academy Award, two British Academy Film Awards, BAFTA Aw ...

won an Academy Award for Best Actor

The Academy Award for Best Actor is an award presented annually by the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences (AMPAS). It has been awarded since the 1st Academy Awards to an actor who has delivered an outstanding performance in a leading ...

for his performance as George VI in the 2010 film ''The King's Speech

''The King's Speech'' is a 2010 historical drama film directed by Tom Hooper and written by David Seidler. Colin Firth plays the future King George VI who, to cope with a stammer, sees Lionel Logue, an Australian speech and language ther ...

''.

Titles, honours and arms

As Duke of York, Albert bore theroyal arms of the United Kingdom

The royal coat of arms of the United Kingdom, also referred to as the royal arms, are the arms of dominion of the British monarch, currently Charles III. They are used by the Government of the United Kingdom and by other The Crown, Crown instit ...

differenced with a label

A label (as distinct from signage) is a piece of paper, plastic film, cloth, metal, or other material affixed to a container or product. Labels are most often affixed to packaging and containers using an adhesive, or sewing when affix ...

of three points argent

In heraldry, argent () is the tincture of silver, and belongs to the class of light tinctures called "metals". It is very frequently depicted as white and usually considered interchangeable with it. In engravings and line drawings, regions to b ...

, the centre point bearing an anchor azure—a difference earlier awarded to his father, George V, when he was Duke of York, and then later awarded to his grandson Prince Andrew, Duke of York

Prince Andrew, Duke of York (Andrew Albert Christian Edward; born 19 February 1960) is a member of the British royal family. He is the third child and second son of Queen Elizabeth II and Prince Philip, Duke of Edinburgh, and a younger bro ...

. As king he bore the royal arms undifferenced.

Issue

Ancestry

Notes

References

Citations

General and cited sources

* * * * * * * * * * * * *External links

George VI

at the website of the Royal Family

George VI

at the website of the

Royal Collection Trust

The Royal Collection of the British royal family is the largest private art collection in the world.

Spread among 13 occupied and historic royal residences in the United Kingdom, the collection is owned by King Charles III and overseen by the ...

*

*

*

*

, -

, -

{{DEFAULTSORT:George 06 Of The United Kingdom

1895 births

1952 deaths

19th-century British people

20th-century British monarchs

Abdication of Edward VIII

Alumni of Trinity College, Cambridge

British Empire in World War II

British field marshals

British people of German descent

British royalty and nobility with disabilities

Burials at St George's Chapel, Windsor Castle

Chief Commanders of the Legion of Merit

Children of George V

Companions of the Liberation

Deaths from coronary thrombosis

Dukes of York

Earls of Inverness

Emperors of India

Field marshals of Australia

Freemasons of the United Grand Lodge of England

Grand Commanders of the Order of the Dannebrog

Grand Cross of the Legion of Honour

3

3

3

Grand Crosses of the Order of Saint-Charles

Grand Crosses of the Order of the Phoenix (Greece)

Heads of state of Australia

Heads of state of Canada

Heads of state of India

Heads of state of New Zealand

Heads of state of Pakistan

Heads of the Commonwealth

Heirs presumptive to the British throne

House of Windsor

Kings of the Irish Free State

Knights Grand Cross of the Military Order of William

Knights Grand Cross of the Order of St Michael and St George

Knights Grand Cross of the Royal Victorian Order

Knights of St Patrick

Knights of the Garter

Knights of the Military Order of Savoy

Knights of the Thistle

Lords High Commissioner to the General Assembly of the Church of Scotland

Marshals of the Royal Air Force

Military personnel from Norfolk

Monarchs of Ceylon

Monarchs in South Africa

Monarchs of the Isle of Man

Monarchs of the United Kingdom

Peers created by George V

People educated at the Royal Naval College, Osborne

People from Sandringham, Norfolk

People of the Victorian era

People with speech disorders

Recipients of the Order of St. Vladimir, 4th class

Residents of White Lodge, Richmond Park

Royal Air Force personnel of World War I

Royal Navy admirals of the fleet

Royal Navy officers of World War I

Royal reburials

Scottish Freemasons

Sons of kings

Sons of emperors

Tobacco-related deaths

World War II political leaders